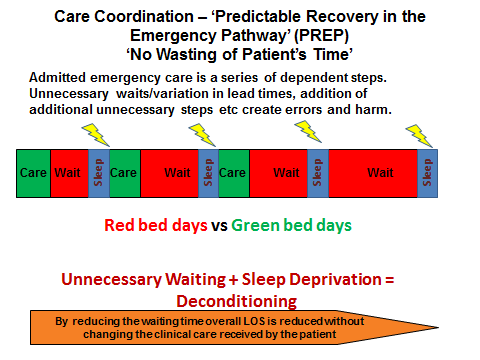

Much of the pathway for patients admitted in an emergency is predictable. The pathway comprises ‘inter-dependent steps’ some of which need to run in ‘series’ whilst others need to run in ‘parallel’, but they are predictable in the majority of cases. Of course, there are patients whose journey is unpredictable due to biological variability, however, it is the unpredictability added by the ‘system’ which adds to the unnecessary prolongation of the pathway, increasing the number of ‘Stranded Patients’. These unnecessary waits in the pathway take many forms, the timeliness, for example, of the construction of a definitive case management plan, ‘necessary’ in-patient diagnostics and interventions, ‘discharge critical’ reviews by other specialties, preparation of discharge documentation and prescriptions as well ‘delayed transfers of care’. The key underlying principles of PREP are ‘Home First’ (see Liz Sargeant’s article - http://wp.me/p5H5EW-1jJ ) and ‘no wasting of patient’s time’. From the patient’s (and their family and carers where appropriate) perspective, knowing the answers to the following 4 questions helps to create a sense of ‘expectation’ in a situation when many patients can feel ‘not in control’:

1. Do I know what is wrong with me or what is being excluded? This requires a competent senior assessment and discussion.

2. What is is going to happen now, later today and tomorrow to get me sorted out? The ‘end to end’ case management plan with specified timelines as to when things ought to happen.

3. What do I need to achieve to get home? The ‘clinical criteria for discharge’, a combination of ‘physiological’ and ‘functional’ parameters. ‘Back to baseline’ is rarely a useful phrase.

4. If my recovery is ideal and there is no unnecessary waiting, when should I expect to go home? This is the ‘expected date of discharge’ which should be set along with the clinical criteria for discharge at the point of admission.

The aim is to get everyone on the ‘same page’. Lack of clarity to the answers to any one of these 4 questions will result in ‘drift’ and ‘hidden waiting’ with frustration and confusion for the patient. Items 3 and 4 together are a ‘co-ordination’ instrument that can be used to ‘flush out’ unnecessary waiting along the pathway.

An interesting exercise is to find out how many of our patients (or their next of kin where relevant) are able to answer these 4 questions within the first few hours of admission. Having done this exercise in a number of organisations, it is usually less than 10%. Why can’t it be much more?

This is particularly important for ‘Patients At Risk of Increased Stay (PARIS), those patients who de-condition/decompensate as a consequence of unnecessary waiting, predominately older people with frailty. It is this de-conditioning which can result in higher care needs which converts a potentially simple discharge in to a ‘complex’ one.

Dr Ian Sturgess - Clinical Director (NHS Emergency Care Improvement Programme) & Associate Medical Director (Monitor)